Your Cart is Empty

Before Anissa Helou was an award-winning journalist, she was an antiques dealer. Specifically, she was an adviser to the Kuwaiti royal family, who between the late-1970s to mid-1980s were building a collection of Islamic art. Her scouting trips took her across the Middle East and North Africa to the Mediterranean, and it was during these travels that she developed a lifelong passion for the foods of the Arab world.

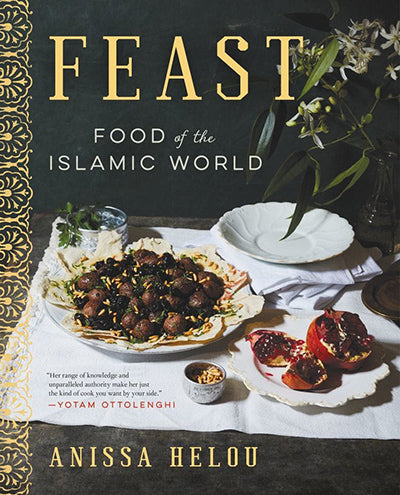

Her first cookbook, published in 1998, chronicled the colorful cuisine of her native Lebanon. In the years since she’s written eight more books, dozens of articles, and appeared on several radio and television programs. But her latest work may be her most definitive. Feast: Food of the Islamic World is a culmination of a life in search of art, food, and culture. Across 500 pages and 300 recipes, Helou covers a globe-spanning array of Muslim cultures, examining their diverse distinctions and how they’ve interacted over the centuries: “The Arabs had control over the spice trade long before the advent of Islam,” she writes, “and they kept this control after they converted to Islam, using the trade to start spreading their new religion beyond Arab lands along the spice trade routes.”

This international spice trade is called the Silk Road, and Helou traverses it in Feast to explore over a dozen cultures. While foods from countries like Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Lebanon are strongly represented, so are ingredients and dishes from Uzbekistan, Senegal, Nigeria, Zanzibar, and Indonesia. Her stories and recipes illuminate regional tastes: fragrant cardamom in the Gulf states, fiery chiles in sub-Saharan Africa, flame-hued saffron in Morocco and Iran. And she illustrates how history and religion have helped shape these tastes over the centuries.

We talked with Helou about the misconceptions people have about food along the Silk Road, and why kebabs seem to show up everywhere she looked.

Feast is a continent-spanning cookbook. What inspired you to write it this way, and now?

Many people and politicians have vilified Islam and Muslims recently, and I felt that was unfair given their rich civilization and ancient culture. These were fantastic empires and beautiful cultures and civilizations. I thought [this book] would be a wonderful way of projecting a positive image onto an often misunderstood religion and people.

And as those empires expanded, so did their access to other ingredients.

Absolutely, and because they became richer and more powerful they lived more magnificently. There were three main culinary strands. The first is Persian: both the mother cuisine and the Abbasids who enlisted Persian chefs to cook in their palaces. The first Arab cooking manuscript was published in the 10th century, apparently for a prince from Aleppo. Almost everywhere you can find some link back to Iran, or ancient Persia, and that cuisine. Take mixing sweet and savory. Cooking meat with fruit is common in Morocco, Turkey, and northern Syria. You don’t really find it in India, but the treatment of rice [in the north’ is similar to the way Persians cooked it.

Then you had the Ottomans in Istanbul, who had separate kitchens specializing in different types of foods like sweets and beats, both at Topkapi Palace and the grand aristocratic houses. Lastly there are the Mughals who ruled India, who had some Persian influences but also their own kind of complex spices.

What are some common dishes shared across these cultures?

One thing they share is kebabs: grilled meat on skewers and grilled fish. And then bread is almost universal everywhere, including in Muslim China. It’s flatbread in endless varieties, either on a flat stone or on the wall of a tandoor oven. In fact, in Uzbekistan they even use the ceiling of the oven, slapping the flatbread up against it, which was quite extraordinary to see.

But in my book I’m not talking about an idea of Islamic cuisine. Rather it is different cuisines of the Islamic world. And finding common grounds in some places and not so common grounds in others.

Do any of these common grounds show up in foods for religious holidays and celebrations?

The first thing would be the killing of the lamb for the big Eid al-Adha. In a lot of different countries you see whole roasted lamb. Biryani is a common celebration dish in India, Pakistan, and even the Gulf. And then you have the sweet and savory tagines. There is a recipe in Feast for m’ruziyah, which is lamb cooked with raisins and honey, which is a typical Eid el-Kabir dish in Morocco. The specifics change according to the country; here in Lebanon the big celebration dish is either a whole lamb or a big joint like a leg with rice cooked with meat and nuts.

How are these traditions reckoning with the modern world? Have you seen modern versions of these dishes as we move forward in history?

They tend to stay pretty traditional. In most of these countries, food is pretty important, and even though there is a movement for youth going for fast food and etcetera, people appreciate their own food. So they cook it the same way.

You do see fast food modernizing, and you have a lot of young people who are not so keen on cooking. If you have enough young people not wanting to cook of course you’re going to lose some culinary traditions and lore. But the interesting thing about most Muslim countries is eventually the young people do get married, and once they get married and start having families, food becomes important to them again. Many of the young girls I talked to, like on the Gulf, were not interested in cooking now, but said that once they get married and start having a family they’re going to start cooking.

Recipes from the Islamic world

Recipe: Meatballs in sour cherry sauce

Recipe: B'stilla (Moroccan pigeon pie)

Jacob Dean is a freelance food and travel writer and psychologist based in New York. He holds a doctorate in psychology and enjoys small international airports, dumplings, and hosting dinner parties. He is also allergic to grasshoppers (the insects, not the mixed drink). You can find him on Instagram and Twitter at @SchadenJake.